19th Century

Buckland: A Center of Innovation

Buckland artisans and business owners manufactured products and engaged in commerce with methods that helped spark America’s early industrial revolution and fostered changes in the region as well. An urgent need: reliable transportation to markets and suppliers not possible on the then primitive roads.

Fauquier and Alexandria Turnpike

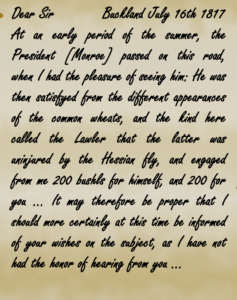

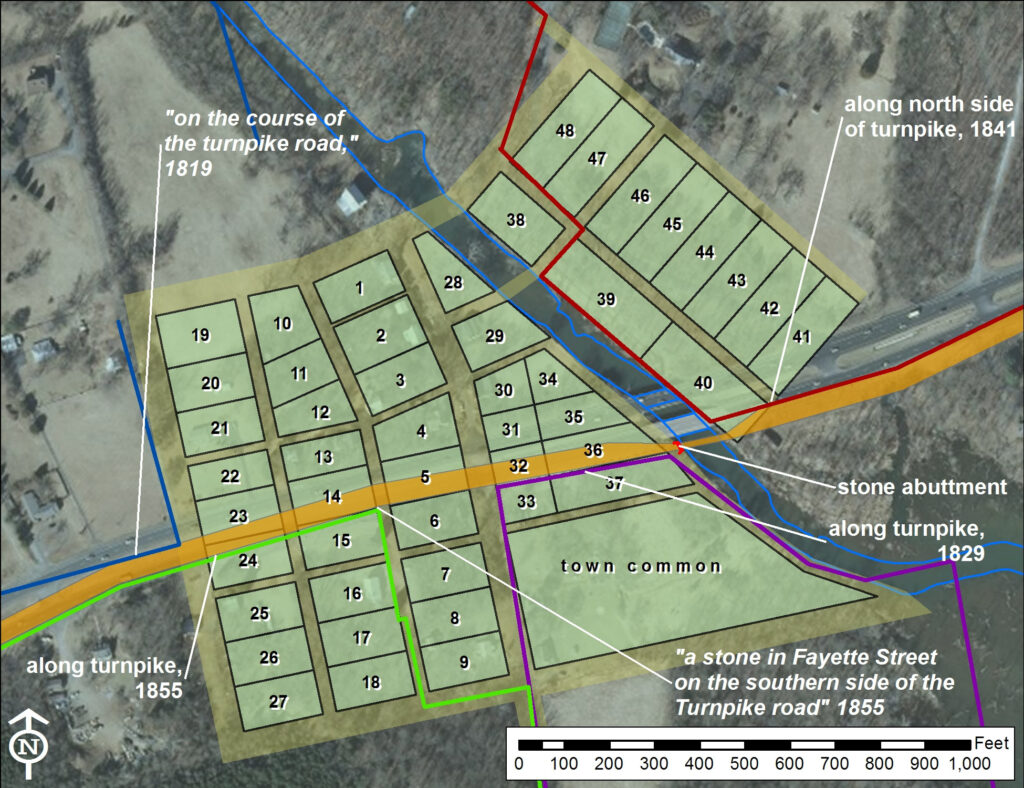

John Love was influential in advocating for better transportation access to the commercial port town of Alexandria on the Potomac River. In 1807 Fauquier and Prince William County citizens petitioned the Virginia General Assembly for a road from Fauquier Courthouse via Buckland to a connection with the Little River Turnpike. The resulting General Assembly act of January 27, 1808 chartered a company “for the purpose of making an artificial turnpike road from Fauquier courthouse to Buckland farm, or Buckland town, and thence to the Little River turnpike road, at the most suitable point for affording a convenient way from Fauquier courthouse to Alexandria.”

Buckland resident George Britton was the Fauquier and Alexandria Turnpike Company’s first president. Later in 1812, he received a contract to build a ten-mile section of the road.

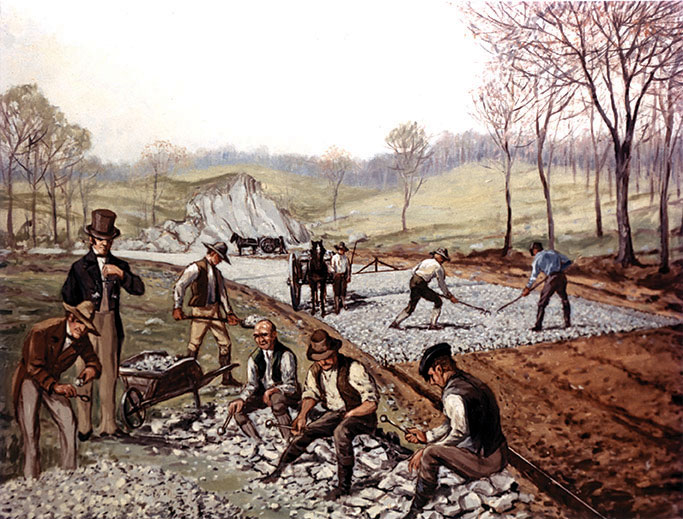

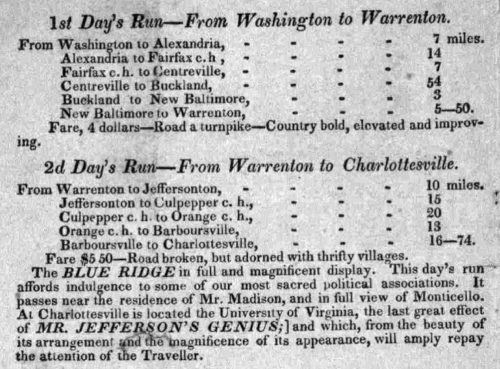

By 1820 the 20 miles of turnpike between Buckland and the Little River Turnpike were completed. It would take another nine years to construct the final eight-mile section from Buckland to Warrenton (incorporated in 1810, formerly Fauquier Courthouse). Under the guidance of Virginia’s new state engineer, Claudius Crozet, construction of that section was done using the newly developed McAdam method: the latest road building technology developed by John Loudoun McAdam of Scotland. The new turnpike section was declared “the best road in Virginia,” and the earlier-built sections similarly ungraded. “Mcadamization” soon became a widely accepted standard in road construction in Virginia and America.

Turnpike right-of-way consumed parts of several town lots. In 1953 the turnpike’s successor, U.S. Route 29, was expanded from two lanes to four separated by a grass median, and carried across Broad Run on a new concrete bridge. The full area of lots 5, 14, 23, 31 and 32 were condemned, their buildings demolished, and their surfaces paved. Several historic structures were lost, but this remains the only ground area of the town’s cultural landscape lost to modern development.

Archaeological investigations in 2012 by Rivanna Archaeological Services documented clear evidence of the original turnpike within the Buckland Historic District.

Mrs. Royall’s Southern Tour

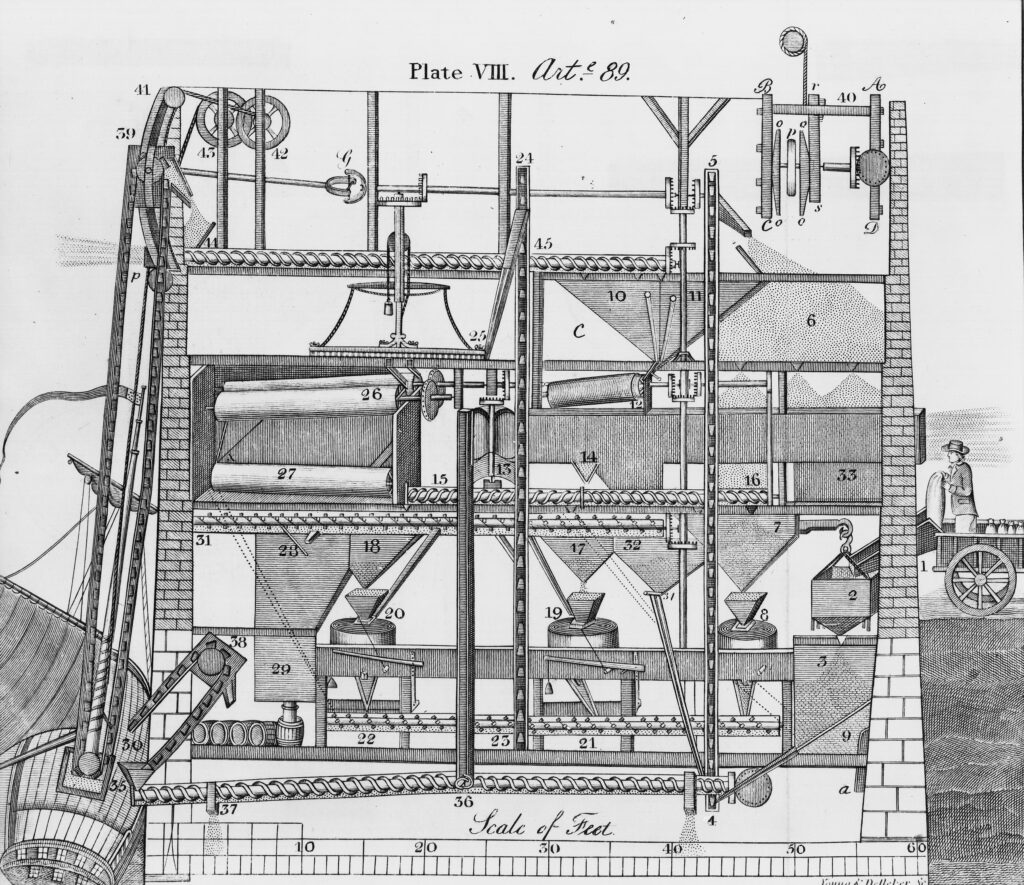

In 1830, Mrs. Anne Royall, a notoriously critical travel writer, followed the road to Buckland. In her book, Mrs. Royall’s Southern Tour, she described the town as “a romantic, lively, business doing village, situated on a rapid, rolling stream … several manufactories are propelled by this stream which adds much to the scenery. Buckland owns the largest distillery I have seen in my travels. The buildings, vats and vessels are quite a show. There is also flour manufactory here on a very extensive scale – the stream is a fund of wealth to the citizens … encompassed with rising grounds and rocks, the roaring of the water-falls, and the town stretching up to the tops of the hills, was truly picturesque.” She further described Buckland as “a real Yankee town for business.”

The Lowell of Prince William

Buckland was also hailed “the Lowell of Prince William” some years later in the Manassas Journal. Constant travel brought new enterprises, such as the Pony Express and William Smith’s Stagecoach Line. By 1835, Buckland was a thriving stagecoach town complete with its own Post Office in 1800 and Stagecoach Inn. Martin’s Gazeteer of Virginia 1835 lists the population, “130 whites; of whom 1 is a physician; and 50 blacks.” The African American residents of Buckland, from the beginning, were skilled laborers. Although most were enslaved, several were free and at least two owned land and slaves of their own in the early nineteenth century.